15 th September , 2019

Recently I attended a talk at the Art Institute of Chicago, about collecting Black contemporary art. The audience was encouraged to ask the panel of prominent artists and collectors questions. A timid voice from the crowd asked the panel, “Black contemporary art seems to be trending right now. It’s very popular in the market. As a young black woman artist, I want to know what the future of Black art is? What’s going to be important for Black artists like myself who are just starting out, 10 years from now? Panel member, New York-based, interdisciplinary artist, Torkwase Dyson, cut through the silence with a poignant offering that not only answered the young artist’s question but helped to further contextualize the art of Black folks. As I paraphrase Dyson’s words…

Maybe we need to step away from this Western idea of a linear procession of time, and think about the circle, the continuum. Afrofuturism is a term used frequently now, but it certainly didn’t begin in this moment, and abstraction is something that Black artists have been in dialogue with since the beginning. So maybe it’s not about thinking about what the future of Black art will be, but considering the future is now, the past is now, it’s all on a continuum in conversation informing the work. So therefore, you decide what the future of art is in what you are creating now.

A silence fell over the auditorium; most of them people of color, and highly influential in the art world. Torkwase Dyson’s powerful and compelling statement put my mind back into the in-person conversation I had a couple of months earlier in the same city, with Houston, Texas native, now Harlem, NYC, based artist, Robert Pruitt.

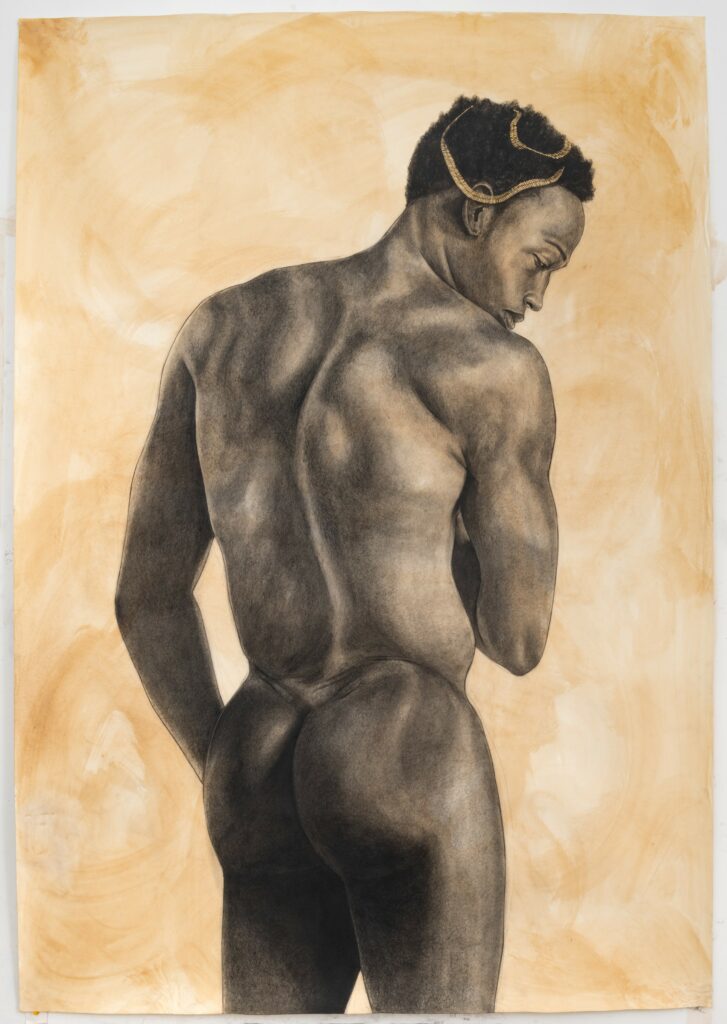

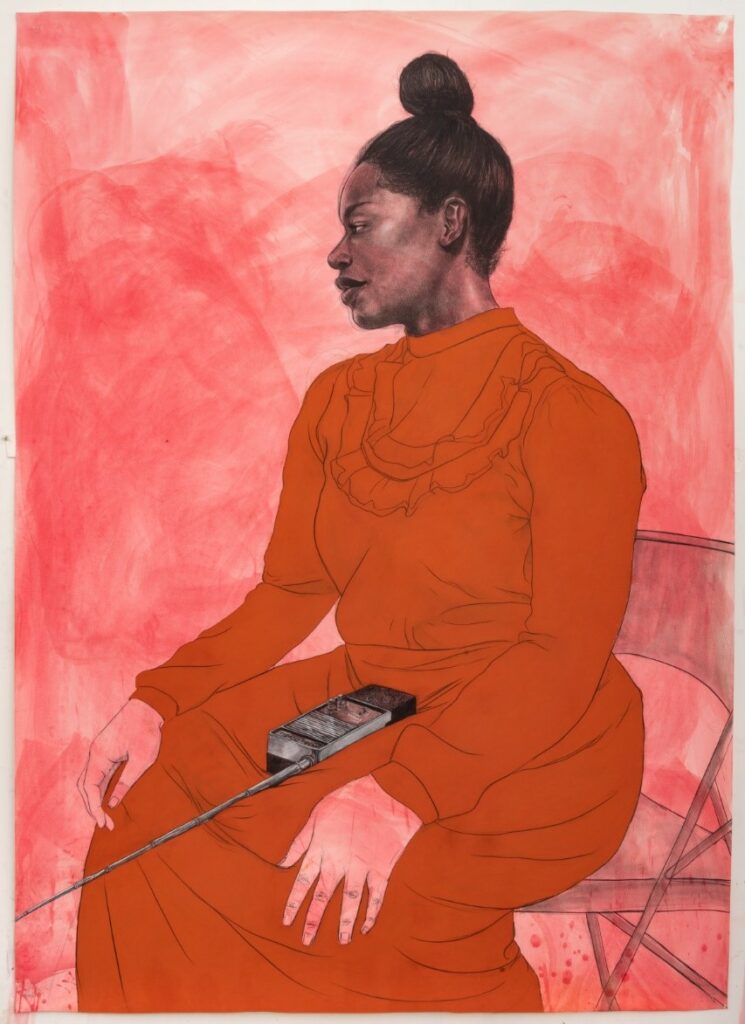

The concept of Black contemporary art being on a continuum, constantly being in dialogue with the past, present, and imaginary future runs heavily through Pruitt’s prolific body of work. I first engaged with Pruitt’s work five years ago when I met him on the campus of The University of Illinois at Chicago. Immediately the term Afrofuturism was applied to the draftsman’s work that figuratively depicts Black people in voids, often alluding to being in another place, maybe echoing the phrase “space is the place” referencing the great experimental jazz musician Sun RA, or maybe they are referencing the Supa Dupa Flyness of Missy Elliot, or just maybe the mothership had landed giving us “the Funk, the whole Funk and nothing but the Funk”, perhaps Pruitt’s work signifies 2Pac with Digital Underground- “Do What You Like”… or maybe, just maybe, his work is somewhere between the folds of Erykah Badu’s towering headwrap suggesting “I’ll See You Next Life Time”, or in the pulsating tenor of Kendrick Lamar repeatedly chanting “Yams!”

Maybe, these figures are in transition, headed to another realm, world, universe. Maybe they are in the Garden of Eden, maybe have accomplished nirvana, maybe they are at home with the ancestor’s in the land of the great Orishas, or maybe they are in heaven. My meditation on where or what the voids Pruitt places his subjects in is a bit futile, because the point is, that they are anywhere, but here. Afrofuturism as a term seems limiting when applied to Pruitt’s work, just like the question posed by the young artist mentioned earlier. Pruitt is not concerned with the future being a distant designation in time, but more as a place, a space, a mindset, and a meditation on the immediacy of now.

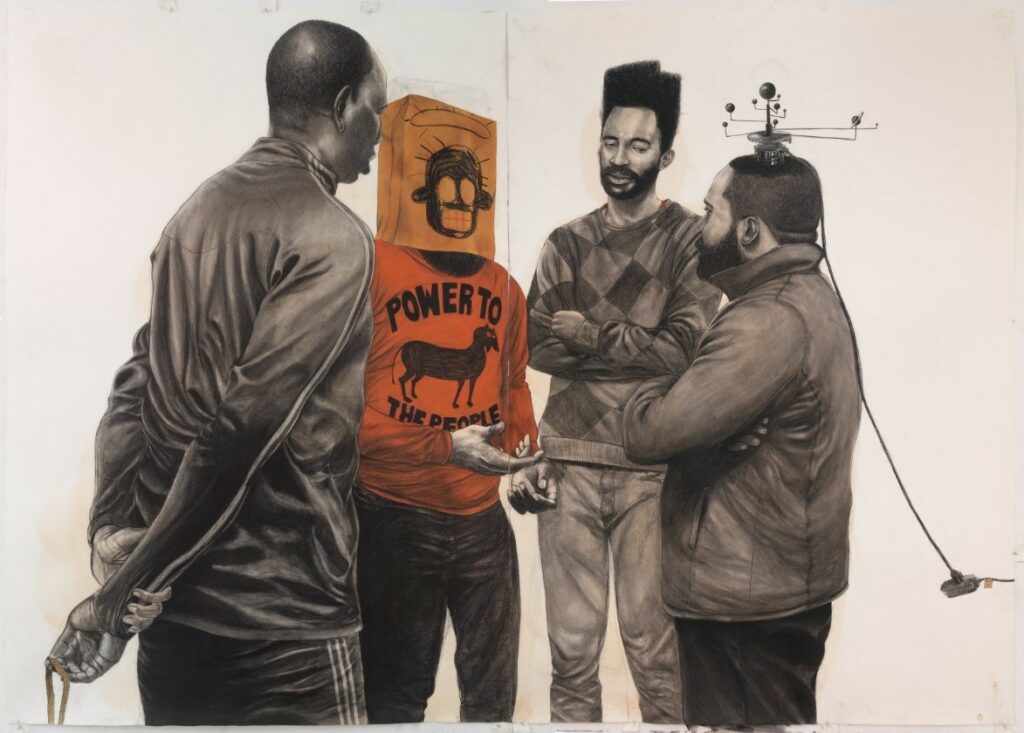

With masterful draftsmanship, Pruitt depicts the rejecting and confrontation of mainstream American society by deifying quotidian iconography of a specific group of people within African American culture. His work attempts to edify what’s considered nonconformist, antiestablishment, ghetto, ratchet, and hood. Like a Renaissance painting depicting a biblical scene, Pruitt gathers pictorial symbols that stand in for words, phrases, and expressions, creating a visual language that places Black people in the center of the cannon of contemporary western art. Pruitt explains this during our conversation:

“I think about the act of someone getting a face full of tattoos. At some point, that was a gesture that would block someone from different lifestyles, and an entry into mainstream society… You weren’t going to get an office job with teardrops tattooed on your face. But I see “hoodness” as a kind of rejection. I want to elevate those things, because that’s the place I grew up in, that’s the kind of blackness I knew. I want to pay homage to the specific imagery I saw, so its nostalgic in a way. And these things are just so–—not white! I am constantly looking for things that feel like that they don’t come from Western culture, from Europe, or mainstream American culture. I look for symbols of what Black people have created in this country that are uniquely ours culturally.”

Black contemporary artists who have influenced Pruitt, including Charles White and John Biggers, deployed symbols of regal African history such as Dogan masks, Ethiopian Coptic crosses, and Egyptian mythology, within their work. Pruitt also engages with classical African iconography because for him it symbolizes pre-colonial Black culture. However, he realized that his use of the symbols was somewhat problematic, and it has caused a shift within his latest work. Pruitt stated, “I think we were using those symbols to make us feel better about the situations we are in within the diaspora— these symbols gave us a sense of culture that otherwise had been taken away from us.” He paused for a moment and said, “But then I started to think about, what about all of the significant culture we created here (The United States) ?!”

“What about the idea that we started to recreate ourselves from scratch?” Pruitt asks. “I’m thinking about how African Americans created a culture and an identity that is specific to this place,” he further explains. Pruitt sites the African American church as a major foundational culture building entity within the Black community. Historically the Black church was a physical safe space, an institutional space that was a formal repository for social, political, and artistic production.

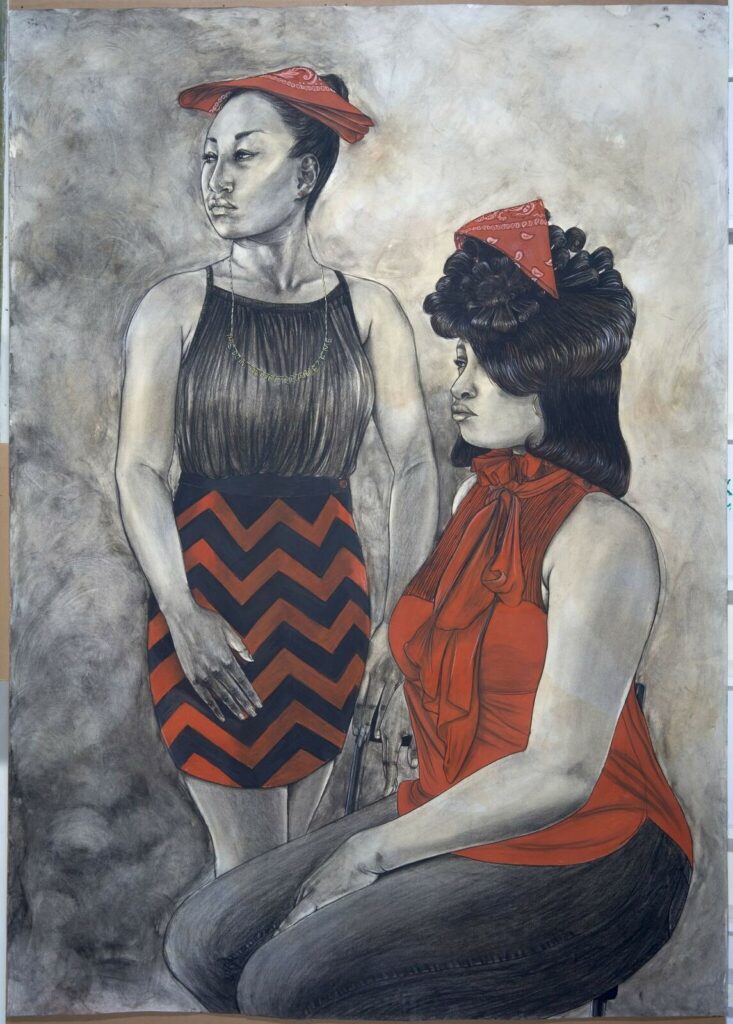

Pruitt attempts to intersect themes of a sacred community with a visual language he creates within his imagery. In Communion, 2018, Pruitt uses the iconography of both Black American church culture and gang culture. Women historically have been the pillars of the church. The women of the composition bring up biblical scenes when two women are central to the narrative, such as Ruth and Naomi, and Mary and Martha. Dressed in contemporary clothes that do not emote feelings of sanctity, the women are poised with red bandannas atop of their heads. This scene initially suggests fellowship, sisterhood, however there is gravity within the subject’s gaze that refuses to connect with the viewer. We have no entrance into this scene that is guarded by the feminine figures. Zooming in highlights a razorblade that is placed in one of the women’s hands, a small detail that alters the entire tone of the work and points to a whole new context. It brings to question, who is not allowed in the scene, and whose gaze is being rejected.

Looking closely at the image it is easy to point out what Pruitt means when he speaks of culture that was created specifically by Black Americans. The hairstyles, jewelry, and styling of the outfits are specific to Pruitt’s aesthetic experience growing up in a Black community in Houston, Texas.

Here he has married the gesture of women covering their heads in houses of worship, be it a “church hat” or the lace head covering resembling crocheted doilies, with the ornamental but socially charged red bandanna, a head covering that can be associate with gang culture. Lines are blurred within Pruitt’s pictorial narrative when representations of Bloods, a well-known gang formed in the early 1970s along with the Crips in Los Angeles, is conflated with Christian beliefs that reference the blood of Christ. “I think race/identity is thought of in very binary terms. I think it falls on how close you are to blackness. Its basic, white is the best and black is the worst in these very elementary terms. And then how you identify yourself and how people identify you is scaled in that spectrum. So I think about the weighted ends of that spectrum. I think it is the destruction of that binary that will give us liberation,” explains Pruitt.

Pruitt, who is not religious, realizes that the Black church is still highly regarded as sacred space, while gang culture is dismissed because of the violence often associated with it. However, Pruitt regards both churches and gangs as communities that created safety for marginalized people, and within these circles of protection, there is a vibrant cultural production. “My upbringing in Houston, and what I saw in the Baptist Church, and elements of gang and street life made my concept of blackness very specific. I had no idea that there were other types of Black people,” Pruitt said.

The material culture of African Americans is not the same as any other group of people within the realm of blackness globally, and Pruitt is very interested in unearthing black resistance within the aesthetics of blackness that he grew up with, such as the practice of wearing a t-shirt with the deceased person’s face and name printed to a funeral. Printed t-shirts, tattoos, piercings, hair coloring or even bandannas are not specific to African Americans, but Pruitt is interested in the specificity of presentations, codes, and uses with the materiality that makes it specific to African Americans who created a culture, created a tribe. “I use different outfits, hairstyles, headdresses, some of them come from my own imagination, along with other objects to create multiple entryways into each figure’s interior world. Each figure’s personal choices of dress and adornment are intended to help the viewer create a narrative about the figure,” Pruitt explained.

Pruitt is creating a pictorial archive of Black material culture, by aggrandizing quotidian life within the cannon of contemporary art. Now the symbols of both “hood life” and church life are able to serve as non-white binaries that bookend a spectrum that is devoid of the white gaze. The imagery creates a new vocabulary that looks within African American cultural production, through the lens of Pruitt’s aesthetics, to affirm and qualify, rather than looking to an external comparison. Pruitt’s compositions present a state of being that is in between departure, and arrival, documenting a journey that is in constant flux, constantly recreating and reconstructing itself, a journey that is between the ancient, and the unknown future, a journey that is not a linear procession of time, but a circle.

The Majesty of Kings Long Dead – Robert Pruitt is on view until September 28, 2019 at Koplin Del Rio Gallery, for more information visit koplindelrio.com.

Follow Robert Pruitt on Instagram at @robertpruitt

*Quotes from the essay are taken from a conversation between Robert Pruitt and Danny Dunson during an in-person interview, in May 2019, and have been edited for the purpose of this article.