18 th July , 2019

Brooklyn NY based Artist Kennedy Yanko guides us through an intimate journey of her process, her connection to materiality, and the intersecting concepts behind her work.

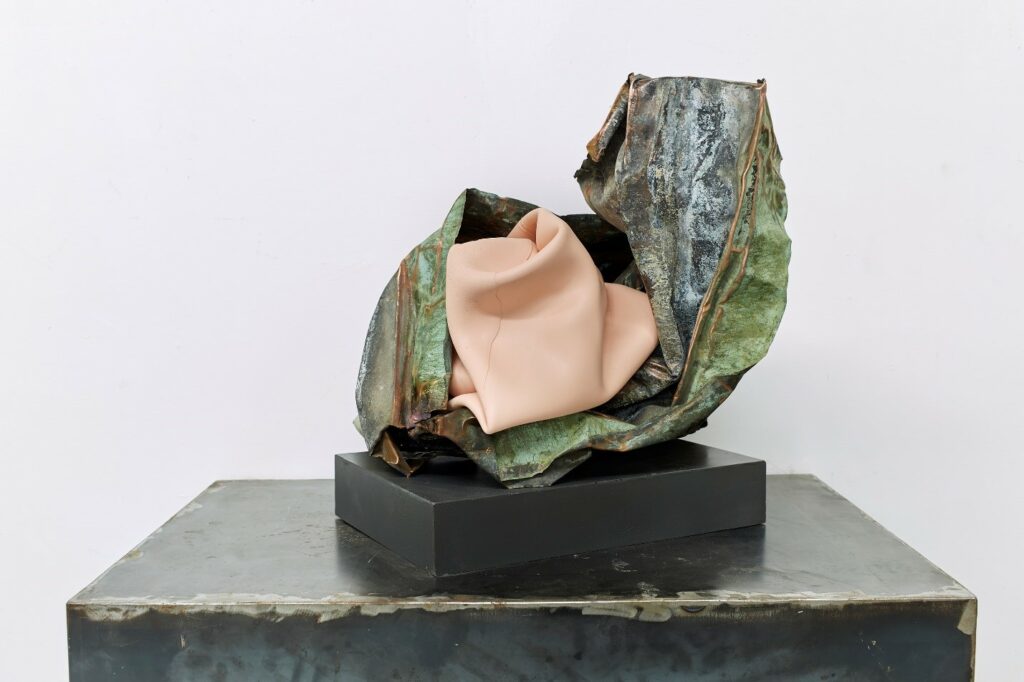

Kennedy Yanko is a sculptor based in Bushwick, Brooklyn. She works fluently in metal and paint, repurposing natural materials in unexpected, lyrical combinations. Her current work explores the limits of material gesture, and simultaneously reveals innate links between seemingly dissimilar objects.

Do you consider yourself to be a sculptor, or do you identify more with a multidisciplinary trajectory?

Two years ago I would’ve told you I’m a painter. I now consider myself a sculptor and introduce myself as such. Although I think of myself as more of a multi-disciplinary artist and I’m currently working with metal and paint skins.

Tell me about the mediums you use. Is there a particular material that you prefer to work with? How do you acquire the materials you use?

I create paint skins, which are – made from paint; (combined with a few additives for ultraviolet protection and archival purposes), to use as a sculptural material. When dry, I use their weight and breadth to form structures. I’ve been working with paint skins for about ten years now, but more recently have used metal as a framework for the paint skins. The metal and skin have such reciprocity; finding metal as a support was a long time coming. I now frequent junk yards and work with demolition teams looking for materials, specifically metal.

Why are they (paint skins and metals) mutually benefiting, what do you mean by reciprocity?

With metal and paint skin, I get to play the part of the trickster. While you may know the distinct, differentiating characteristics between metal and paint, I like to make you question where one part begins and another ends. I like confusing the eye and forcing you to use your different kinds of intellect to figure it out. Which elements are heavy? Which are light? What part is metal? What is paint skin? My being able to play with perception is dependent on the materials’ dialogue. Their contrast is what joins them. Without it, we’re less likely to truly examine each material’s contents and expand the way we think we understand them. We’re less likely to understand the metal as support–a foundation–for the paint skin. But in realizing the value that each component highlights in the other, we realize their reciprocity.

How has your background and life experiences informed the work you are doing?

I grew up thinking I was an artist. I took watercolor classes with 80-year old ladies at age 5 and was taking printmaking classes with my dad at night in a community college when I was 13. There was always a place for me when I was creating, a special quiet place to explore and get lost, creating was my reprieve from the world.

Everything I create is digestion of what I see around me, in my day-to-day, travels, visual interactions, and conversations. My upcoming solo show, “HANNAH,” is about the markings of our pasts, and what happens when we’re dependent on our identities, titles, and perceptions. Often times, we let our narratives paralyze us and close ourselves off to opportunities for expansion and evolution.

I’m amazed by the incredible softness and malleability your work takes on. There is a corporeal quality to your forms. You make metal appear as skin, bodily organs, or fabric. Tell me about this concept, and how you came about making work in this manner.

I used to study and teach Hun Yuan Chi Gong. The body and its ephemerality was always at the forefront of those teachings. When I was painting on canvas and rubber, my practice was very physical and aggressive. The movement captured in that work looked as if time had been frozen, and whatever was going on within me at that moment was left there for everyone to see. I use my body to understand things; it’s like there’s an antenna within me that can answer any question I have.

Even though the process of creating my art is now different, there are certain configurations that continually appear, and the gesture being made is still intensely physical. I choose the materials that I do because I feel they’re able to successfully translate this kind of sensory language. They have lives of their own to be captured in time, and they express how they wish to be seen. Sure, I’m making decisions and manipulating them in certain ways, but I am foremost a conduit for these materials. I sit with them in a formal dialogue before understanding what shifts need to take place and how they will present conceptually.

I love how found objects and paint skins–together–embody how fleeting and transient our perceptions of things can be.

“Uses power tools and lip-gloss at the same damn time!” I find this quote from your Instagram post to be quite poignant. As a woman artist, how often do you find that the art world is more focused on you, your identity, your womanhood, your striking physicality, rather than the functions of your work?

You’re essentially asking, “how do you do what you do and have a pussy at the same time?”

But the real irony here, is that this question is another way of highlighting my sex and imagea and drugs. Regardless, it’s important for us to talk about so that the next generation of female artists won’t have to. I can’t imagine what women artists had to deal with 20 or 50 years ago. The stories I’ve heard are heart-wrenching. God bless them for their perseverance and patience.

Until recently women’s work was rarely understood for its content or surrounding practice. Focusing on her background or husband or skin color is a superficial way of avoiding serious inquiry into her as a person, or as a significant influence.

As a woman of color, I have to continually corral the questions and dialogue around my work. I have to protect my story and make sure there’s consistency in what is being said and told. I can’t expect or assume anyone knows or understands what I’m trying to do or say. There are only brief yet exhilarating moments in time when another person is completely on the same page as you. Outside of those blips of connection, we are teaching and learning from each other.

I think what can be helpful to shift this superficiality, is aware of what is being asked, and HOW it’s being asked. When someone asks me, “as a female artist, how are you lifting up such heavy things?” or, “how are you sifting through junkyards all day and prancing around in stilettos at night?” my silent glance speaks volumes and communicates that I can do and be whatever I want to do and be.

But my physical ability in taking these actions (lifting metal) isn’t really the question that people mean to ask. They want to know where we–artists with pussys–find the freedom and courage to do what we do.

Anyway, like I said, we’re all learning and have to be able to help move these messages along, so the conversation is productive and not isolating. I’ve definitely asked seriously inappropriate and unthoughtful questions and learned from that.

Referencing the quote in the previous question, there are so many qualities of your work that align with both masculine and feminine attributes. How much of this is an allegory of the self?

I do my best to recontextualize the materials that come into my studio, I let their history inform their existence, but it doesn’t dictate their current state. You miss this incredible opportunity to

discover something new when you reference everything you’ve known in trying to understand an object. When we try to decipher and analyze instead of feeling and sensing, we limit ourselves. As Barnett Newman says, encounters are “metaphysical events” to be respected.

“When you meet a person, you have an immediate impact. You don’t have to start looking at details. When you meet someone for the first time your reaction is a total reaction. In which the entire personality of a person and your own personality make contact. That’s a metaphysical event. If you have to start examining the eyelashes and all that sort of thing, it becomes a cosmetic situation which you will remove yourself from the experience.” BN

The work is me, in its entirety. It’s what I see. It’s what I do. None of what I do alludes or gestures towards the masculine and feminine. But the human inclination is to title and categorize things to better understand them–so I guess the masculine/feminine attribution is an attempt in offering “language.”

I’m more interested in what happens in that sweet spot when seemingly paradoxical things begin to integrate. I have my first museum solo show this fall, Before Words (September 2019, Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts) that grapple with the tendency to over-intellectualize our approach to an experience. Here’s an excerpt from some writing I’m working on for this exhibit that might help elaborate on my thoughts:

“Abstraction is the intuitive tool that illuminates independent thought…Vision ultimately fails us when we depend on sight alone…When we complicate our most personal experiences with others’ interpretations, we compromise the sanctity of what it means to be an individual.”

When we zero in on the masculine and feminine of something, that’s meant to be an integrative whole, we eliminate the magic that happens within this harmony and miss the mark.

On the concept of creation, you deploy unconventional materials to make forms that appear to be organic, breathing, but not representing forms found in nature. It’s like you are returning man-made materials back to the earth, back to nature. I am wrong with this analysis? Are you recreating “creation”?

I won’t take credit for recreating “creation,” but you’re right about my intention to recognize nature as the source of all things. I’m returning human ownership to the universe. We mine and pull everything from the earth with little respect or acknowledgment towards what it takes to provide these incredible gifts. When people look at metal, they see it as this thing that they drive in every day or that they type with or cook with or answer calls with. But with a shift in perspective, you realize that both you and these inanimate objects are made from atoms.

This work is about oneness, it vibrates with life because it is imbued with it.

There is a performative nature to your process, Tell me about how your connection to performance and material came about.

Over the years I’ve taken in as much information as I could get my hands on relating to the physical body, the ethereal body, and the history that repeatedly shows how our external world is a demonstration of our internal worlds. I’ve always had this undeniable clarity and certainty around the information I take in through my physical body, to the extent that my intellectual, conceptual grasp served as an affirmation of what was already there.

But performance and material have never gone hand in hand for me. I understand the power of motion, and as I’ve mentioned, I appreciate how a gesture can so authentically capture a moment in time…but performance isn’t an aspect of my process. If anything, it’s a material that I sometimes choose to use.

In many pieces such as Holy Worked, viewers must also perform in a sense, to fully experience your work. The piece requires the viewer to bend, tilt, squint, walk around, zoom in, and zoom out. How much is this intentional from your point of view of making? How much is the viewer engaging with the process of your work, even when it’s displayed?

I never really intended for that, but I like that people are doing that! What you’re describing, is having to experience the work the way an artist does. Have you ever gone to a museum or show with an artist? The first thing we do is walk straight up to the work, look at the side, try to look underneath…we’re absorbing it in its totality, and trying to figure out how it was made (lol). This is the beauty and fun of sculpture: it’s multifaceted, and every side has a different face to it. It takes you in. Which, you know, might make sculpture more feminine in nature than masculine- -they’ve had it wrong this whole time! haha – sorry Richard!

Hopefully, people will engage this initial pull they feel and seek to know and understand more. By following that urge to discover, perhaps they’ll become curious about their own evolution in consciousness. And just maybe, in that moment, if only for a moment, that person can overcome the great divide of otherness, diving into the suchness of we.

Upcoming Events for Kennedy Yanko

- Solo show, HANNAH, at Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago, Illinois. (opens 9/18)

- Solo show, Before Words, at the Urban Institute for Contemporary Art, Grand Rapids, Michigan. (opens 9/26)

- First public sculpture installation, “Three Ways,” being installed as part of the Poydras Corridor Sculpture Exhibition funded by The Helis Foundation. New Orleans, Louisiana.

For more information please visit https://kennedyyanko.com/