22 th December , 2019

Representation Matters, Black Love, Black Joy, Black Girl Magic, these phrases have flooded social media timelines for the last five years or so, and let’s face it, social media is a powerful tool that is influencing society on several levels. It’s clear, to me at least, that hashtags are driven by real-life thoughts, that cover many topics within the human experience. Artists often take up problems of society and attempt to create a language that explains, heals, reinterprets, educates, historicizes, creates empathy, and so on. Black contemporary artists are charged with this task and actualize these themes in ways that have caught the attention of the artworld’s commercial market at large, all the way down to the person who has never been interested in art before.

With painting always being a focus for historians, gallerists, museums, and aficionados, much attention has been paid to the canvas. But what happens when the contemporary art market becomes over-saturated with repeated visual and conceptual themes, when figurative imagery dominates the market, and brown skin visualized by Black contemporary artists and non-black artists alike, becomes redundant cliché, and most of all, excessively derivative? Oddly, I feel that something opposite happens to what many would assumingly call a decline in artistic production. Artists do not abandon their perspective practices or the formal qualities and concepts that inspire and move them to create. Alternatively, out of redundancy, overconsumption, and the same tropes being deployed adnauseam, comes forth work that is fresh, surprisingly different, historically referential, and most importantly, innovative and nuanced. The viewer whose eyes grew weary of seeing the same thing, starts to pay attention to details, as stated in the well-known adage, “the devil is in the details”, and so it is with a young vanguard of Black contemporary artists who instead of abandoning the figure, have found ways to keep figurative painting as fresh as social media hashtags, which as annoying as they might be, hashtags are created on the pulse of contemporary life, revealing the true zeitgeist of the times we live in.

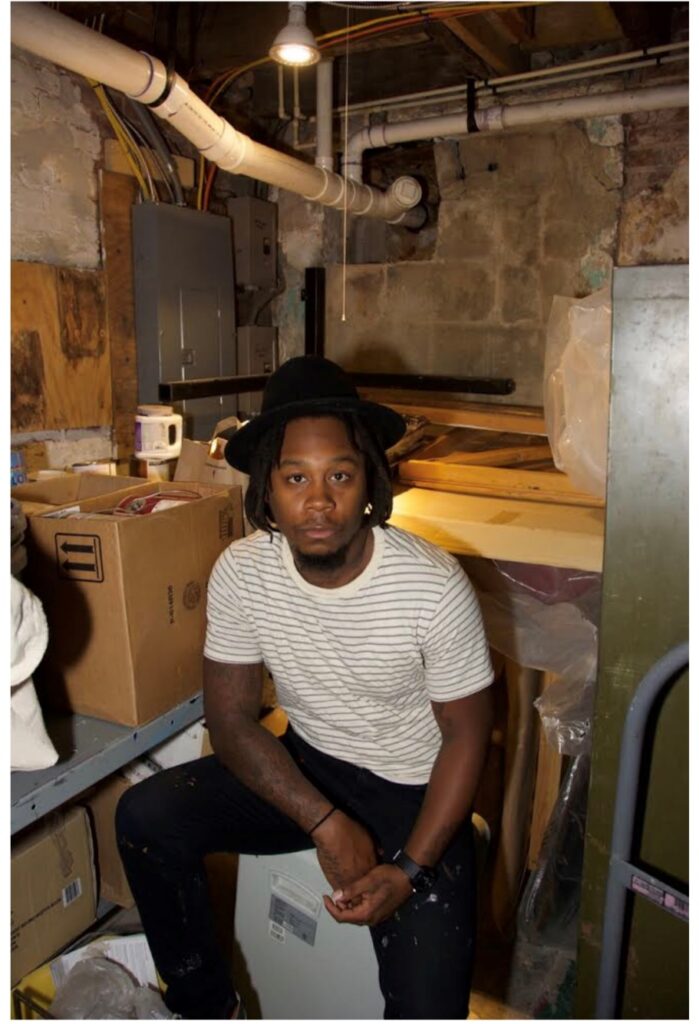

Currently, an MFA student of Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) is making an impact with his image-making. Prior to graduate school, Jerrell Gibbs was self-taught, and says that ninety percent of his training was based in experience, while about ten percent is grounded in theory. His self-studies and research lead him to a myriad of books that he had read over a long period, in his autodidactic pursuit of the art of painting. “I believe spending more time understanding the business of art gave me the opportunity to advance at a much faster pace”, explains Gibbs, who is currently represented by Mariane Ibrahim Gallery (Chicago). Though Gibbs has been practicing art professionally for the last five years, he always thought of himself as an artist, and never imagined doing anything else. “I’ve always felt that I had a creative side to me, even if at the time I hadn’t fully explored it. It was something that was innate”, explains Gibbs.

In the studio, Gibb’s routine is fairly consistent as he primarily works with oil paint on linen or canvas. “What I love about oil is the tactility of it. I love the historical aspect as well. I am a history buff, so I love the fact that oil has longevity, it has been used for hundreds of years and still has relevance.” The artist admits to loving the smell of oil paint, but most of all, Gibbs loves that oil paint has the ability to take on a character of its own once it is applied to the canvas. This is an attribute that he has not found with other mediums.

“My biggest goal as a visual artist is to stay authentic”, says Gibbs. As he explains his goals as an artist within the following quote:

“I’ve seen so many artists conform and box themselves in a corner for various reasons. I just want to stay true to myself and my practice. I want to continue to challenge myself as a painter and not get comfortable with what I know how to do. I’d like to continue to challenge myself by exploring the unknown within my work. That thing that’s not necessarily easy to do. I want to continue to learn something new each day, as a painter and as a human.”

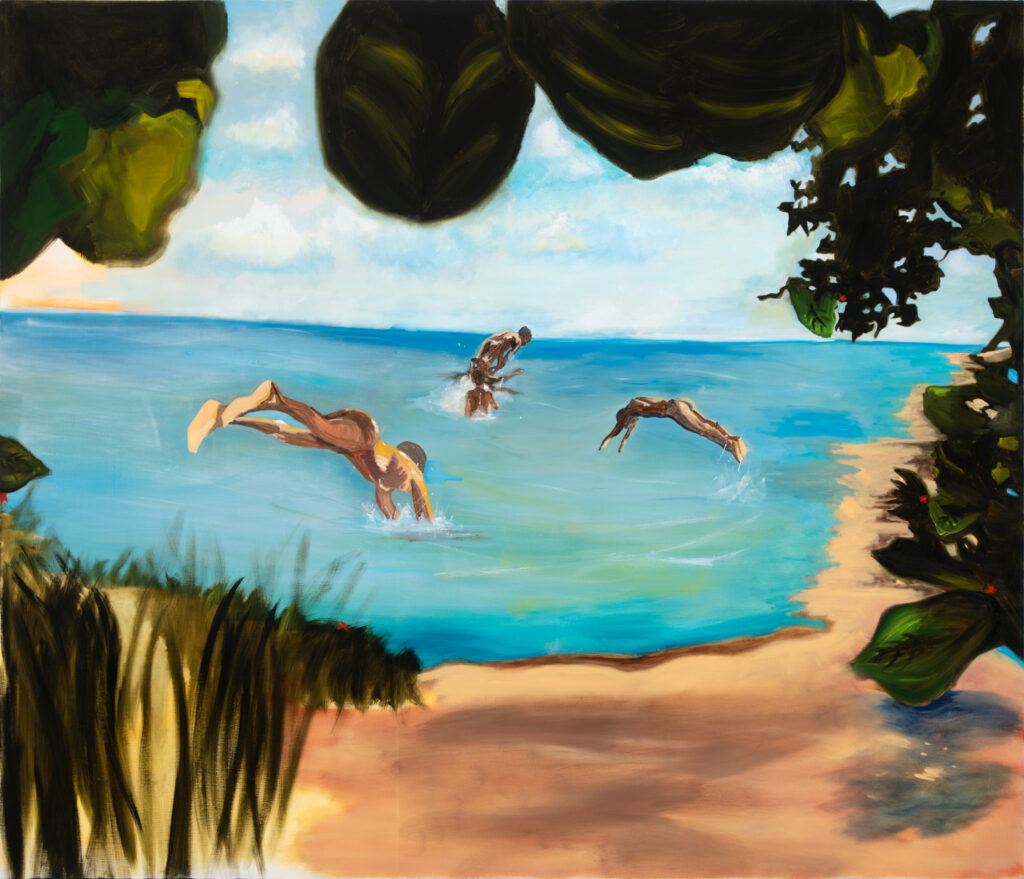

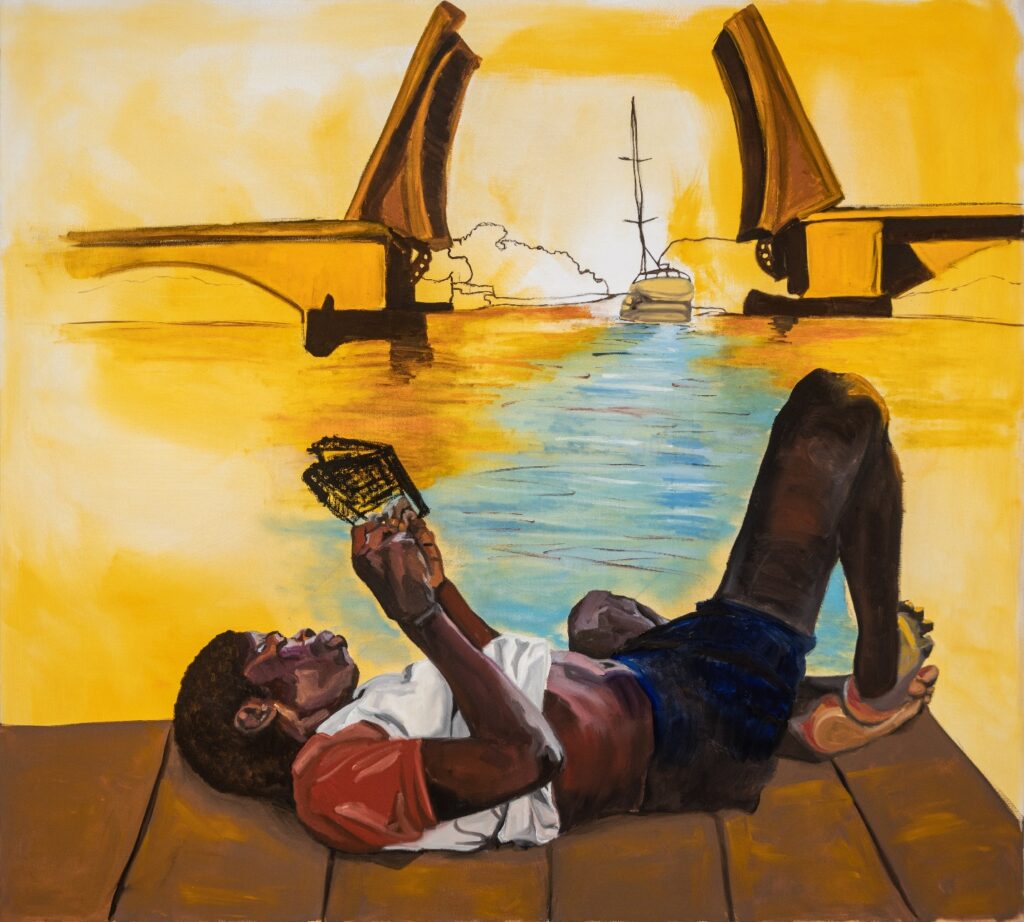

Gibbs credits a long list of acclaimed artists who have inspired him, fellow Baltimore native Derrick Adams, Noah Davis, Henry Taylor, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Benny Andrews, Alice Neel, Alma Thomas, Jacob Lawrence, Henri Matisse, Diego Velázquez, and many others. One glance at his work and its easy to recognize how Gibbs’s formal style is in dialogue with these great painters. What is new and different lay in the subtleties The meanings and concepts behind his most recent body of work are centered around representing universal humanity often not shown in depictions of Black life. Gibbs’s current series of paintings is a meditation on the joy of simply being left alone. These compositions pictorialize Black people in isolation without fear of being violated or othered. The scenes focus on a joy that is seemingly independent of systemic racism that regulates ordinary freedoms. A joy that is often experienced by majority powers and is too often considered a privilege rather than a universal human right.

While conceptualizing these quotidian scenes, Gibbs considered making imagery that would counter the current portrayal of Black people throughout mass media.

“Black people have been portrayed in a stereotypical manner, and my work strives to alter that perception. I believe we as Black and Brown people have to take control of our own narrative, our own identity, and in order to do so we have to revise how our people have been depicted in various art forms, the news, movies, television shows, on social media, etcetera.”

Gibbs’s quest to normalize Black bodies through his use of narrative has a simple formula—focus on the love. Like many contemporary artists, Gibbs is concerned with depicting blackness that attempts to isolate from the white gaze, a blackness that functions autonomously to elevate Black culture and essentially depicts the various depts of Black love. In an open letter that voiced his thoughts on his nephew’s future in the racially charged United States, first published in Progressive Magazine in 1962, James Baldwin wrote to his nephew of this same name, recalling the day he was born… “Here you were to be loved. To be loved, baby, hard at once and forever to strengthen you against the loveless world….

“Remember that. I know how black it looks today for you. It looked black that day too. Yes, we were trembling. We have not stopped trembling yet, but if we had not loved each other, none of us would have survived, and now you must survive because we love you and for the sake of your children and your children’s children.”

Although he was speaking directly to his beloved nephew, Baldwin’s words “…but if we had not loved each other, none of us would have survived…” continue to resound loudly, speaking towards the collective lived, inherited, and witnessed the experience of Black Americans, and Black people globally. Gibb’s work does not intend to serve as a healing antidote to systemic racism, but it does offer an alternative space and place for the eye, and psyche to rest. I think the hashtag for this concept is #selfcare. Selfcare is not a new term, but millennials have unapologetically proclaimed and practice self-care in ways that contest cultural constructions that suggest one should work themselves to the bone, and sleep when dead.

Selfcare practices by young artists like Gibbs filters what they allow themselves to over-consume, such as black bodies violently violated by the police, and the frequency of stereotypical negatively charged narratives of the Black community. Contemporary self-care demands that mental health care is not a white thing, it is not a rich people’s thing but is a necessary concern for all people, and Black and Brown people have traumas that have been devalued, overlooked, ignored that need to be addressed with acute healthcare.

This series is not merely a grouping of feelgood motifs meant to appease the rage of an oppressed people, conceptually they demystify concepts of Black/Afro-Futurism which often time presents outer space, and technological advancements as a means to create and acquire utopianism, a depiction which can often be misconstrued as escapism. Gibb’s series of everyday scenes are timeless, free of generational and stylistic decay, offering simplistic scenes of tranquility that many Black and Brown people have not been able to experience.

Consider the painting, In the Trees, 2019, a Black couple joyously barbeques, nothing major, but we all should recall a woman seen in a viral video calling the police on a group of black people who were barbecuing at an Oakland park. The sardonically named “BBQ Becky” was identified later as the Stanford University-educated environmental scientist, Jennifer Schulte. Consider the painting, Top Down, 2019, that depicts a youthful male, reading a book, while laying in sublime leisure, again nothing major. But some of us will recall earlier this year when a white Ph.D. student called the police on a Yale University graduate student, who was napping in a dorm common room while studying for finals.

Deep within the sweet, nostalgic, romanticism of Gibb’s work, is an ardent desire for the ability to freely breathe, to exist without extremities, without fear based on one’s identity, as the artist simply put it, “to just be normal”. Perhaps that is why this critic finds the work to be refreshing, and critically necessary, I cannot think of anything more human, more normal than love… for if we had not loved each other, none of us would have survived.

Gibbs’s work was recently featured in Expo Chicago, and currently on view in two exhibitions: “Our World & Tropical Diaspora”, curated by Derrick Adams and Thomas James on view until January 18, 2020, at The Eubie Blake National Jazz Institute and Cultural Center in Baltimore; and “Disembodiment”, an exhibition featuring six young, emerging Black American Artists, at UTA Artist Space in Beverly Hills on view until January 25, 2020. Curated by Mariane Ibrahim Lenhardt, of Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.