25 th April , 2019

Who is the artist?

Brittney Leeanne Williams is a Chicago-based artist, originally from Los Angeles. Her work has been exhibited in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami (Untitled Art Fair), and Venice, Italy (Venice Biennale), as well as in Chicago and throughout the Midwest.

Williams attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (2017) and The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2008-09). She is a Joan Mitchell Foundation grant recipient. Williams was a 2017-2018 artist-in-residence at the University of Chicago (CSRPC/Arts + Public Life) and has held residencies at Chicago Artists Coalition (HATCH Projects) and Hyde Park Art Center (The Center Program). Her set design for the short film Self-Deportation has been featured at film festivals nationwide and internationally, including Anthology Film Archives (NYC) and the Pineapple Underground Film Festival (Hong Kong).

Why are these figures so big?

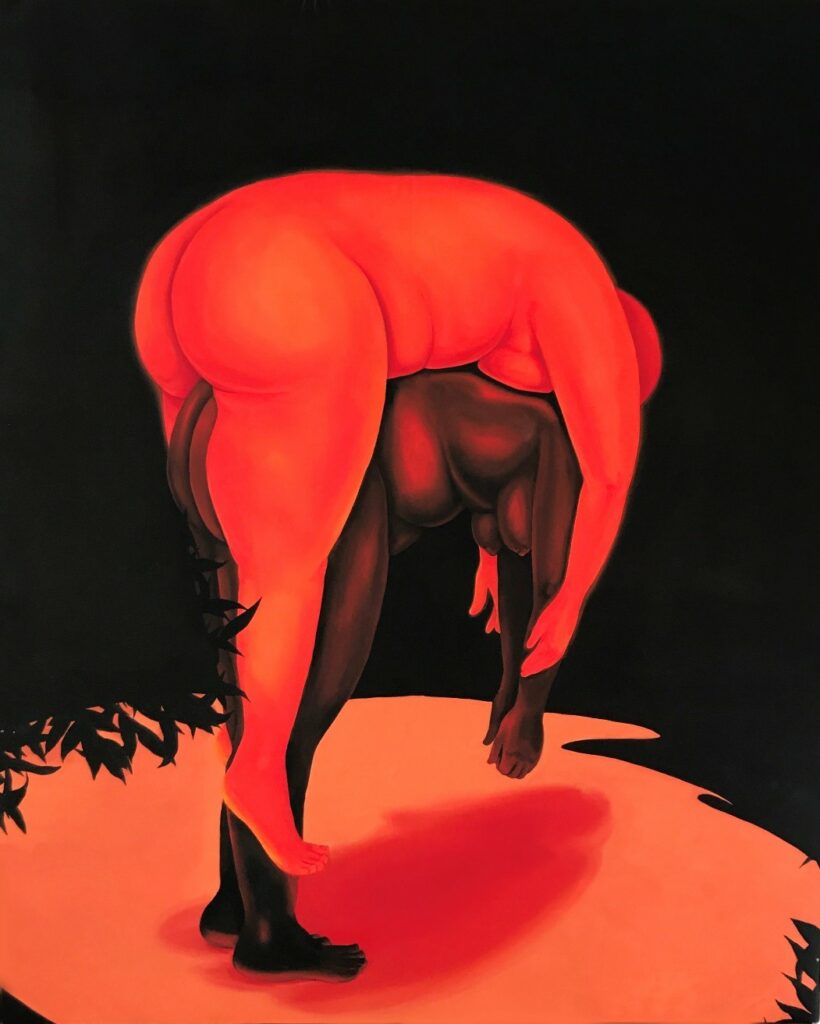

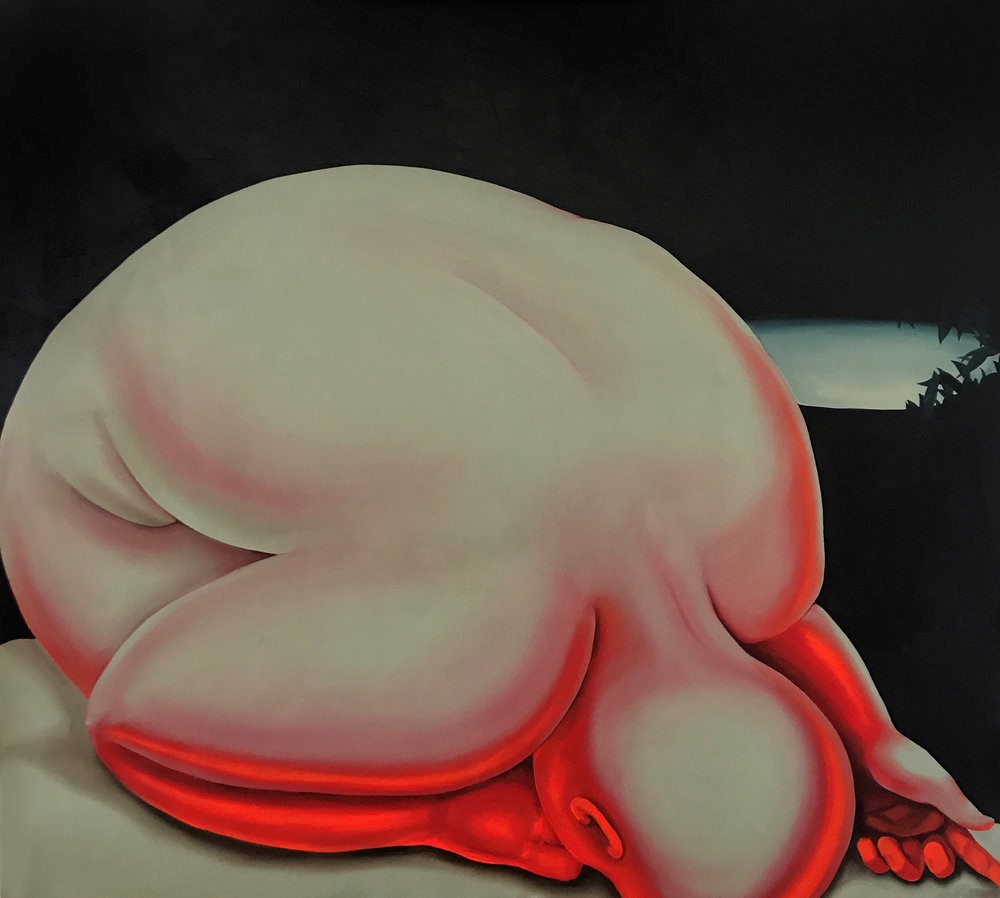

Brittney Leeanne Williams has dramatically captured the female form with emotional dexterity. Voluptuous, sumptuous, whole and substantial sized bodies dominate her canvases. The forms poetically contradict their bigness with an emanating gracefulness, fragility, and vulnerability.

The red female figure that has emerged in recent works is an amalgamation of Black women in the artist’s family that she is very close to. The red, bald, faceless female form is a vessel containing generational experiences of women relatives and the artist as well.

What’s up with the missing faces?

Williams considers these images to be a part of a collective experience of Black women, therefore removing the face, removes specificity and allows viewers to personally connect with the work. There is a delicate balance between these forms’ anchored positionality and the deep care and preciousness that visually takes place within the narrative.

Williams is interested in unseen psychological states, and she uses external articulations of the body to reveal what is going on internally. Think of the concept of smiling and laughing on the outside, while dealing with a lot of pain on the inside. In this series of work, Williams brings internal trauma, and emotional anguish to the forefront, but instead of depicting it on the face, like in traditional portraiture, she uses the body to tell the story. “When I think of states of trauma, or states of heaviness that I’ve been in, my body doesn’t reveal what is actually taking place. So, this kind of bent over, contorted pose (seen in the series) reveals to the viewer what is taking place internally,” explains Williams.

Why red bodies?

Williams has taken away three elements that art viewers have traditionally used to identify Black female representation: hair, facial features, and skin tone. Williams explains that the use of red tones to depict the female form works in a few different ways. First, she is interested in stripping the body of traditional aesthetics associated with blackness, to deflect the biases used to read Black skin. The body becomes liberated but remains a colored body.

Because the artist is interested in trauma and burden, she became obsessed with the red light of ambulances and began to focus on what she calls an “emergency state of exhaustion”. “When I think of these emergency states of urgent exhaustion, I think of Black women like my grandmother, who were never allowed to declare that they were exhausted without it getting dismissed or passed over. I thought of how all the cars on the road will stop and pullover for the red light of an ambulance. So, I thought, if I make the body red, like a glaring siren, she will light up the painting! She will not be dismissed,” said Williams.

Why are the women bald?

It’s easy to assume that Williams’s use of the bald head on female forms is a social and political statement that challenges ideas of patriarchy, conventional beauty, femininity, and womanhood. However, the artist explains, she is happy that viewers can extract that from the work, but that was not her immediate intention.

“I was raised by a woman who had a shaved head my whole life; my mom informed my perspective around beauty standards. I always feel that a shaved head is a very feminine gesture. So, because of that, I thought my figures should be molded into the standards of beauty that my mother bestowed upon me. So, it’s not supposed to be a confrontational statement against conventional Black beauty standards, but it’s more of a gesture towards the beauty of my mother.”

Who is the artist influenced by?

Williams is inspired by the writings of Hermann Hesse and is currently reading Steppenwolf, a novel by the German-Swiss writer, originally published in 1927. “It’s a book about a man that has an animal within him, and this internal push and pulls. I’m just drawn to his way of speaking about spirituality,” the artist said. Williams also credits her mother for introducing her to art as a way for Williams to deal with challenges in early learning in the following quote:

“I was diagnosed with dyslexia when I was in third grade, and it was difficult, very difficult. I had great tutors, but my mom was convinced that I needed to find an outlet that showed me that I was smart and that I had a specialty. We tried different things, but I started to have a strong interest in making art. So, my family would take me to the Norton Simon Museum all the time. Being exposed to Monet in the third/fourth grade, let me know that I wanted to be an artist. It was when I realized that art didn’t have to look like a photograph, and those moments really informed my art making. So then in High School, my teacher told me to look up Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, and Kara Walker. I remember looking at Kara Walker’s work and thinking, we can be that provocative, we can be that confrontational. And that being an option, had a major impact on me.”

Williams is also spiritually moved by the work of painter Jennifer Packer, and photographer Laura Aguilar, two women artists whose figurative works are situated between portraiture, narrative, and landscape.

What is happening in these paintings? What is the story?

In the past, the artist directed her attention to elements of communal trauma within the Black Community while taking on heavy subjects like lynching. The current work examines trauma in a very intimate way.

Williams wanted to explore what she calls “a silent violence” that happened to women in her family, and herself. She is unsure if “violence” is the correct word to use, but she wants to highlight the kind of everyday hardships that Black women experience, such as poverty, and single parenting. One of the repeated visual motifs that emerge in the series is the red slumped figure. This figure appears strong and agile, full of emotion as if she is holding on to years of pain, yet still surviving. Williams considers how often Black women face myriads of challenges alone, therefore the images are often placed as a tableau in front of a sublime landscape, rooting them to the ground.

One of the most traumatic experiences of Williams life was the death of her father at age fourteen. This vacancy caused a ripple effect of events that created a sense of loss, isolation, and burden. Some of the figures in Williams compositions are stacked on top of each other, symbolizing generational blessings and curses, as well as familial support and the heaviness of obligation.

“I am fascinated with my mother being a widow, raising three kids, while being a caregiver to my grandmother at the same time, who was suffering from dementia.”

Though the work of this series focuses on the female form, Williams feels the presence of her father in the depicted grounds and landscapes of the paintings.

Check out the official website to see more of Brittney Leanne Williams’ work, and upcoming projects.