26 th November , 2019

In the last decade, the Black female body has come to the fore within different modalities of image-making. Contemporary artists Wangechi Mutu, Kara Walker, and Simone Leigh, to name a few, have brought black woman subjectivity to the forefront, infiltrating institutional and monumental settings with work that disrupts Western beauty standards, interrogates historical narratives, and promotes a mythology that is connected to both a past and contemporary Black imagination and cosmology. In 2019, the before mentioned artists activated space by taking up space sculpturally, charging significant environments where the remembrance and value of black women’s cultural currency is often erased, taken for granted, or outright ignored.

Florine Démosthène creates imagery that takes up a different kind of space. The work is primarily done on paper, or canvas, not sculpturally in the round, or composed as installation. However, her work is in strong dialogue with these women creators who I deign to call legends. Through a very involved process, Démosthène deposits her own body within the pictorial plane to promote a visual language that depends on black female exterritorial corporeal renderings, to expose, interrogate, and contemplate, the mystical and spiritual happenings of the interior.

Démosthène’s central figure is full-figured, female, and bald. The figure appears continuously, often taking on different positions and gestures simultaneously within composite portraits. “I came up with the idea of looking at a heroine figure way before Wakanda,” she laughed, referring to the popular film Black Panther which highlights women warriors. “I was trying to find something that I could work with for a long period of time and not get bored. Before, I was going through pop culture, and drawing images, but I felt like that was rapidly running its course. I needed to find something to give me a foundation, and during my first trip to Ghana that’s what I found.”

Several years ago, Démosthène, a native New Yorker of Hattian descent, ventured to several countries in Africa, spending the most time in the continent’s cultural hotbed, Ghana. Ghana is a place known for its rich history and artistic production, as well as political activism, being the first African country to become independent from colonialism, under the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah. For African Diasporans, the place is well known as a locale of origin, be it resulting from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, or contemporary migration. For many Diasporans, Ghana is the first place that welcomes them “home”. Diasporans experience this home with a complicated mix of culture shock and the warmest hospitality known under the sun, as well as bold confrontations with the ghosts and living legacies of colonialism, slavery, and antiblackness, causing them to contemplate the realization that maybe this new home, in many ways, is like the home they left. Démosthène admits to having a bittersweet, sweet-bitter, experience living in Ghana, however the time there connected her with ultimately what she was looking for.

“I found a story!” she said. I was writing everything in a journal. I gave myself a year to come up with something inspiring, or I would stop doing art.” Démosthène began to connect with an ancient worldview, spiritual and social practices that commune with ancestors and deities. After spending nine months in Ghana the story that would be the foundation of her current work came to her. Ironically the lead heroine that the artist was in search of, was a manifestation of her own body.

“After talking to so many people and making friends, I realized that there is this internal process that we never discuss. Like what happens if we realize we can levitate (internally)? What would it be like to talk about what happens in the mind mentally and spiritually? Changes happen first within the mind and the spirit. The bulk of my work has been a constant break down of the layers between the world we live in and the spiritual realm.”

Through her investigation of mind, spirit, and body, the artist has been abstracting her own form, as well as stripping back layers of Western norms that she feels are in complete opposition to the thriving of people of African descent. This is a serious endeavor that is constant and draining. It is a kind of violent relearning of self by excavating through mounds of systemic debris, that has been kept in place for centuries to fortify and preserve an agenda of oppression and supremacy. But what happens when we realize we can levitate, a question asked by the artist who has found freedom with the compositions she’s created. The central character mutates into anthropomorphic forms, transfiguring from the human identity of the author, into an inaccessible deity. In other words Démosthène has created a safe space.

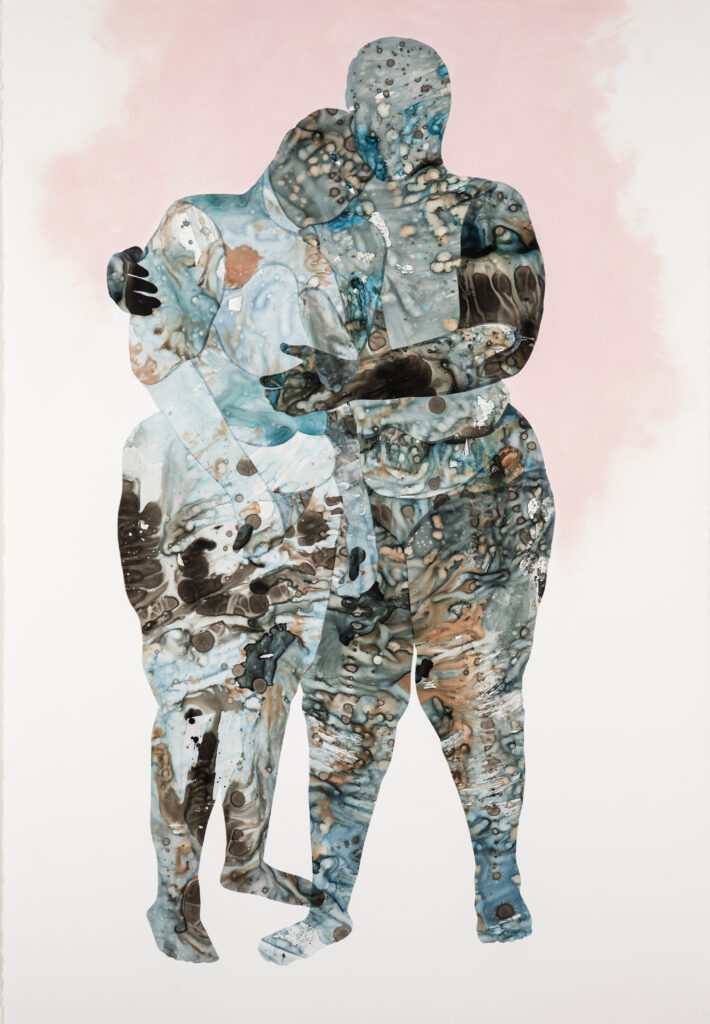

Though this work has a sense of gravitas, there are many elements that have an uncanny ability to bring lightheartedness and a culturally collective understanding of the artist’s sense of humor. “The process has been this kind of shedding and shedding, and pulling away and pulling away, and I’ve seen the work change over time. A lot of it tends to be tongue in cheek. Like I started thinking about the power of the booty.” Démosthène says as we exchange a knowing smile and chuckle. “I didn’t realize the power of the booty until I lived in Ghana for four years. Whenever I entered a room I would get noticed, my booty would get noticed. I felt powerful! I get totally different responses to my body in Africa than I do in the US.” Body positivity is another concept found within the work. Sculptural celestial mounds make up bodily forms that are voluptuous, dense, yet simultaneously very ethereal, instantly changing notions that these concepts are in opposition. These images come after the artist’s awareness and reckoning of her own beauty. “So, I started making sketches while wondering what it would be like if you could harness the power of the booty. I started thinking about this cataclysmic ass that could do things like stop time by clapping its cheeks; a cataclysmic ass-clap! What if we could ass-clap into another dimension or something,” she laughs again.

As Démosthène constantly unveils her heroine which often takes on oceanic aesthetic properties associated with Yemoja and other traditional African religious deities known for their beauty, she still must reckon with her own body that is being used as a template. During the preparation of her latest exhibition, Between Possibility and Actuality (Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago), she began to scrutinize what she referred to as a stubborn love handle. She wanted it gone and she was devastated that she wasn’t able to diet and exercise the love handle away in time for her next gallery opening. Finally, it donned on her that the very thing she was scrutinizing in the real, she was magnifying and glorifying in her compositions. “All that anxiety over something that no one cares about!” she laughed. “But this is the process of the work, as I pull back layer after layer, there is this ongoing conversation, this constant push and pull that lets me know I have much more work to do.”

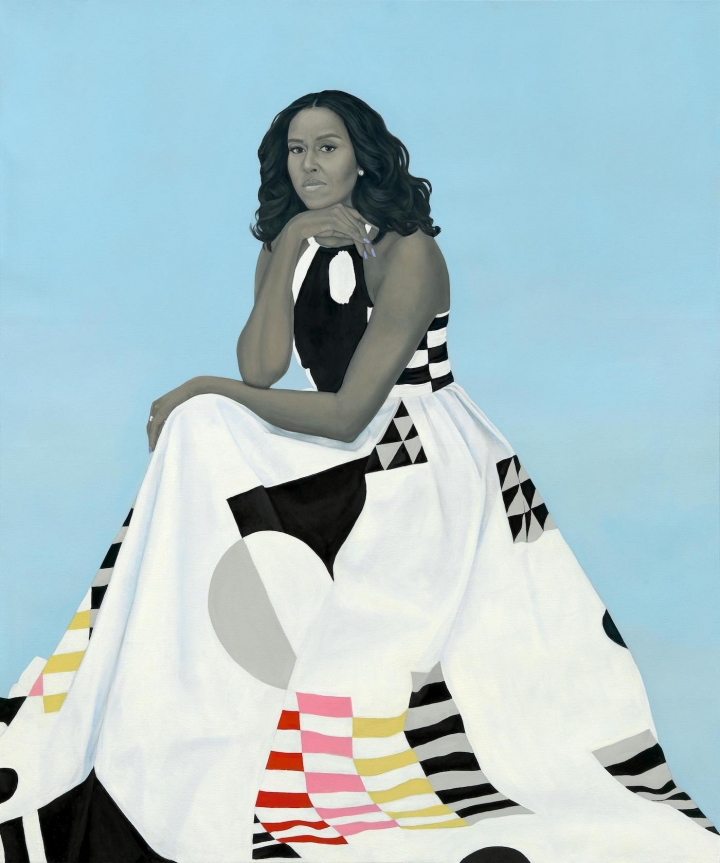

Though the forms Démosthène uses are based on her own likeness, she has erased some specificities that directly connect to her. Amy Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama, disrupted familiar image-making when the artist took away certain specificities of the iconic former First Lady of the US. In Sherald’s painting, the skin tone is composed of flattening and softening hues that take Mrs. Obama’s rich warm brown flesh tones to shades that appear tinted and grayed. The luster and deepness of her melanin was replaced by tones, that once examined closely, are not commonly found in real skin. Sherald’s painting actively shifts Michelle Obama from the designation of an accessible person that could be picked apart and scrutinized, to the aspirational and inaccessible designation of deity. This artistic move replaces Mrs. Obama’s familiar and accessible photo-realistic image that was and still is, consumed ad nauseum, often met with both praise and disdain, to an otherworldly realm. I am likening this otherworldly realm to the same space that Démosthène’s work creates, a safe space where one can levitate.

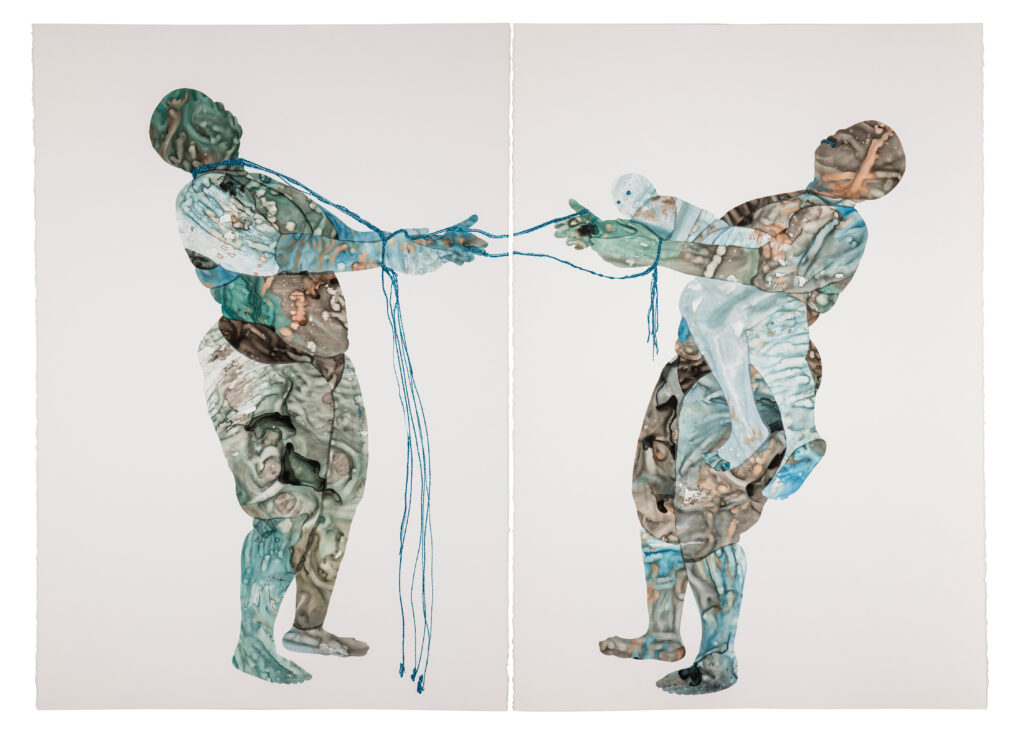

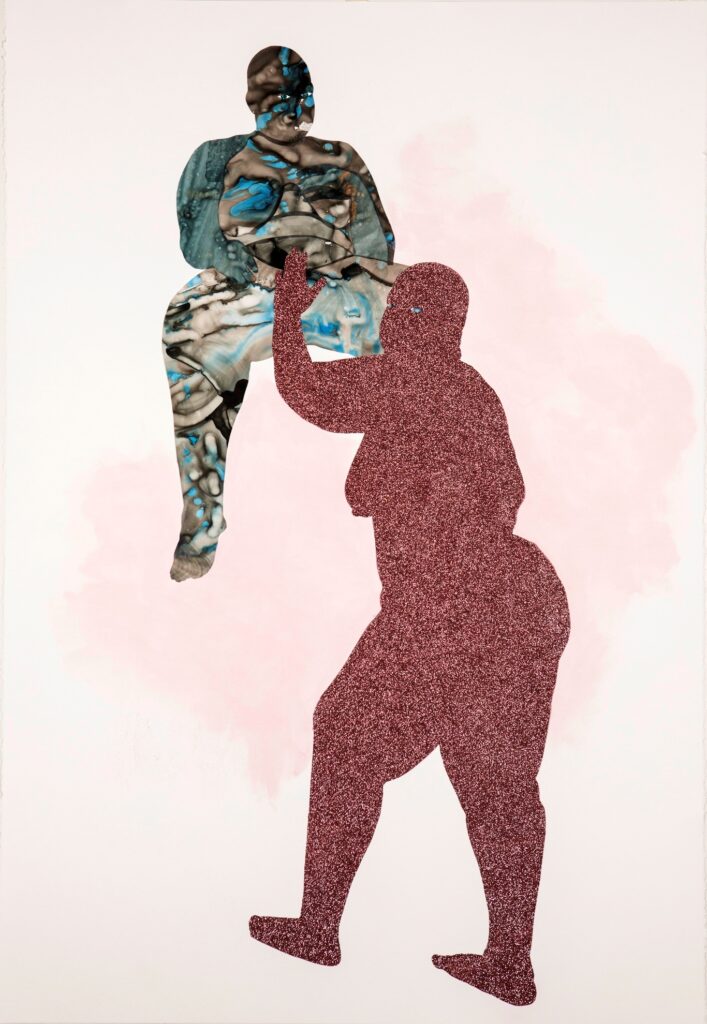

Démosthène’s figures are composed of different colored inks, concentrated water colors on mylar, that in reaction, create a marbling effect. Depending on the themes in which she is contemplating at the moment, a pallet of soft hues usually deriving from blues and blacks is used. The process starts off as a digital collage of selected self-portraits the artist photographs using a timer. This collage only serves as a point of reference, a template in which the composite, multivalent, portraits are fleshed out, and is never seen by the public. The final works have all been rendered using ink and mylar, transferred to paper or canvas, then going through several detailed processes of layering and sealing. Glitter is often added later, creating the texture of appliquéd textile.

Démosthène constantly considers both the scale of the figures and how they gaze out to the viewer. In this latest series, forms engage with each other, as well as peer out in ways that safeguard the forms within the composition, while resisting the gaze of the viewer. An example of this is the work titled Remembering My Future (2019). Here, Démosthène’s heroine has morphed into two forms, one of her signature marbled ink technique that appears translucent, the other, an opaque silhouette made of sparkling pink glitter. “A lot of times I’m thinking about what the body would look like as a silhouette. Can I just give you a silhouette and you can figure everything else out? A strong silhouette has the power to convey more information sometimes than a fully realized form,” Démosthène explains. Since the artist works primarily with a limited pallet in order to focus on form and composition, the application of glitter serves as a texturizing medium as well as supplemental color. “My ancestors come to me in dreams, laughing, because they know I am stubborn. That’s what that glitter figure is, it’s an ancestor stopping me from my own undoing, quieting, and shielding me from the outside voices of self-doubt, as I safely levitate, as I claim my own power.

We all have these ideas of what life is supposed to be, what things are supposed to happen and how things are supposed to go. And then they don’t work out that way. And we have to decide to relinquish these ideas, realizing that we really don’t have any control, and move forward and trust the energy of things. Or we choose to hold on and stagnate ourselves. I had a lot of clear-cut ideas about things I want, and I just had to let go of a lot of it. I started remembering my future. In the past I was thinking about my future, but now that moment is in the past. I have to actively remember my future. I often think about all the pacing, anxiety, and frustration I experienced in the past trying to get the right representation as an artist. When I surrendered all of those western ideals and connected to my power within—the power of my ancestors, it happened, like overnight.

In order to experience the fullness of Démosthène’s work, I had to let go of a lot. Like the narratives of the work, I was confronted with conversations with the self. I had to let go of Western constructs of feminine idealism, body image, religion, and societal norms. I had to retreat within the dreamscapes, the aquatic voids, the duplicated twin-like bodies, and the sumptuous layers of roundness, sparkle, and muted tones. Once I did, I realized, that I too, was able to levitate.

Florine Démosthène’s solo exhibition Between Possibility and Actuality is currently on view at Mariane Ibrahim Gallery (Chicago), until December 21, 2019

All quotes have been taken from an in-person interview between artist Florine Démosthène and Danny Dunson, editor-in-chief of ArtX, November 2019.